When Sonny Liston stepped into the ring in Miami Beach on February 25, 1964, he was widely expected to leave it the way he entered: as heavyweight champion of the world. Of the top 10 ranked contenders at heavyweight, he had beaten eight of them, seven by knockout. Those who hadn’t faced him appeared in no hurry to do so: the manager of British champion Henry Cooper said that “We don’t even want to meet Liston walking down the same street.”

Liston, an ex-con who had learned to box in the Missouri State Penitentiary, was a brooding, bludgeoning, bully of a fighter. Strongly muscled, he was considered all but unbeatable: the one loss he had suffered in his 36 pro bouts was relatively early in his career, on points, and had been avenged twice. Cleveland Williams had been swatted aside in three rounds and then, 11 months later, in two. Zora Folley similarly was stopped in the third.

Reportedly, President John F. Kennedy had urged champion Floyd Patterson not to defend against Liston because of the latter’s strong ties to the Mob, a direction that Patterson and his trainer Cus D’Amato had willingly followed, not least because they anticipated the likely outcome. Indeed, when Patterson could evade him no longer and put his title on the line in September 1962, Liston dispensed with him in the opening round. In July 1963, Patterson attempted to regain his crown; once again, he was beaten inside three minutes.

Now Liston was about to make his second defense; and if America – specifically, white America – found Liston terrifying, it wasn't exactly enamored of his brash young challenger, either.

Cassius Marcellus Clay from Louisville, Kentucky was the opposite of Liston in almost every way: he was fast of feet, hands, and mouth. He didn’t box the way heavyweight champions were supposed to fight; nor did he comport himself like one. The “Louisville Lip,” they called the braggadocious youngster; Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times predicted that his challenge of Liston would be “the most popular fight since Hitler and Stalin – 180 million Americans rooting for a double knockout.”

Yet while many expected a knockout, there was little to no doubt which one of the two would be on the wrong end of it. Clay had won light heavyweight gold at the 1960 Rome Olympics and was undefeated in 19 contests as a professional. But he had been decked by journeyman Sonny Banks early in his career, had squeaked past contender Doug Jones by decision two fights previously, and in his most recent outing had been floored and left in all kinds of trouble by Cooper, before rallying to stop the Englishman on cuts.

Adding to that belief was Clay’s behavior at the weigh-in. As soon as Liston appeared, the challenger seemed to lose his mind. “I’m ready to rumble now!” he yelled. “I can beat you anytime, chump! You’re scared, chump!” He lunged toward Liston in an apparent attempt to attack the champion right then and there, as a group of people, including Sugar Ray Robinson, tried to hold him back. Some of those in attendance wondered if Clay was having a seizure, while others assumed it was the act of a terrified man. Few saw that, amid the melee, Clay glanced at Robinson and winked.

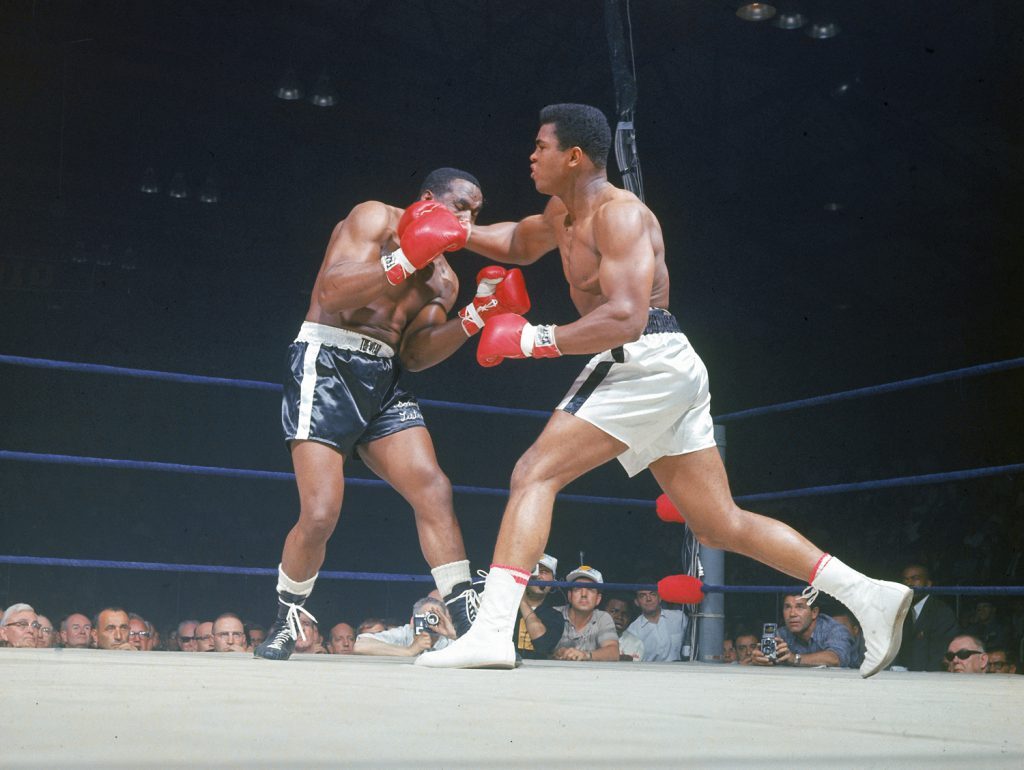

And then the bell rang and the fight began, and Clay danced and moved, and pulled his head back from Liston’s punches. And then he popped the champion with a lead right hand. And another. Liston chased after Clay, Clay retreated and then started popping a swift, snapping jab in his face. Then another lead right stopped Liston in his tracks. Then came a left and another right and suddenly Liston was looking uncomfortable.

The second round was more of the same. So was the third: Liston chasing, swinging, missing; Clay backing up, dancing, dodging, jabbing, and then suddenly standing firm and unleashing a furious flurry that ricocheted off Liston’s face. At the end of round three, Liston was cut under one eye and bleeding from his nose.

The fourth repeated the pattern until, suddenly, Clay started complaining that he couldn’t see. Most likely, coagulant that Liston’s corner had placed on his cuts had been transferred, via Clay’s gloves, to the challenger’s eye. He returned to the corner pleading with his team to cut off his gloves, but trainer Angelo Dundee sat him down, started rinsing his boxer’s eyes with a sponge, then shoved his mouthpiece back in and told him to spend the fifth round running until his vision cleared.

Which is just what Clay did – or tried to do. But Liston was on the attack now and landed a thudding left hook flush on the young challenger’s jaw. But Clay shook it off, and by round’s end he was back to bouncing on his toes and snapping out his jab. The moment had passed, and as he walked slowly back to his corner at the end of the round, Liston seemed to sense it.

In the sixth, Clay continued to spear Liston with lefts and rights, the champion now following him around half-heartedly and throwing little of any consequence. And when the round ended, Liston trudged to his stool, sat down, and stayed there.

Cassius Clay was the heavyweight champion of the world.

Because it was boxing, and particularly given Liston’s Mob ties, there were and remain doubts expressed about the outcome, as there were and are about the rematch 15 months later.

But Clay didn’t care.

“I don’t have a mark on my face, and I upset Sonny Liston, and I just turned twenty-two years old,” he exclaimed to Howard Cosell in the ring afterward. I must be the greatest ... I shook up the world! I’m the king of the world!”

The following day, Clay announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam and was now Cassius X; within a week, he had become Muhammad Ali.

Boxing would never be the same again.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (10)