Thirty-five years on from the International Boxing Hall of Fame first opening its doors and beginning the process of determining the inductees for its inaugural 1990 class, there is one — and only one — thing about the IBHOF that everyone with an interest in the museum in Canastota, New York can agree on: Manny Pacquiao deserves to, and will, go in next June.

Every other detail regarding the process and the people under consideration for entry is up for debate.

And in certain cases, and when it comes to certain folks with a passion for the sport, fierce debate.

Boxing is not a sport in which statistics tell the bulk of the story. There’s no 500-homer or 3,000-hit benchmark; there’s a lot of “eye test” involved when you’re talking about a ballot that includes some athletes who competed professionally on fewer than 30 occasions. In boxing, if an individual contest goes the distance, subjective interpretations separate winner from loser. So how could deciding who gains entry in the sport’s Hall of Fame be anything but an exercise in subjectivity?

Halls of fame take a variety of different approaches to induction. Baseball, requiring that 75 per cent or more of the voters tick off a name, is considered by many to not be inclusive enough. Basketball is widely considered too inclusive, its honoree list dotted with players who weren’t among the very best of their own time, never mind all-time. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ought to either change its criteria or its name, because Dolly Parton, Jay-Z, and the Bee Gees sure as hell ain’t rock and roll.

The bottom line is that deciding who goes into any hall of fame isn’t an exact science, and it’s impossible to please everyone.

That said, with IBHOF ballots currently in voters’ hands, due by the end of October, the time seems right to take a close look and explore possible changes to the process that could inch us ever so slightly closer to pleasing everyone.

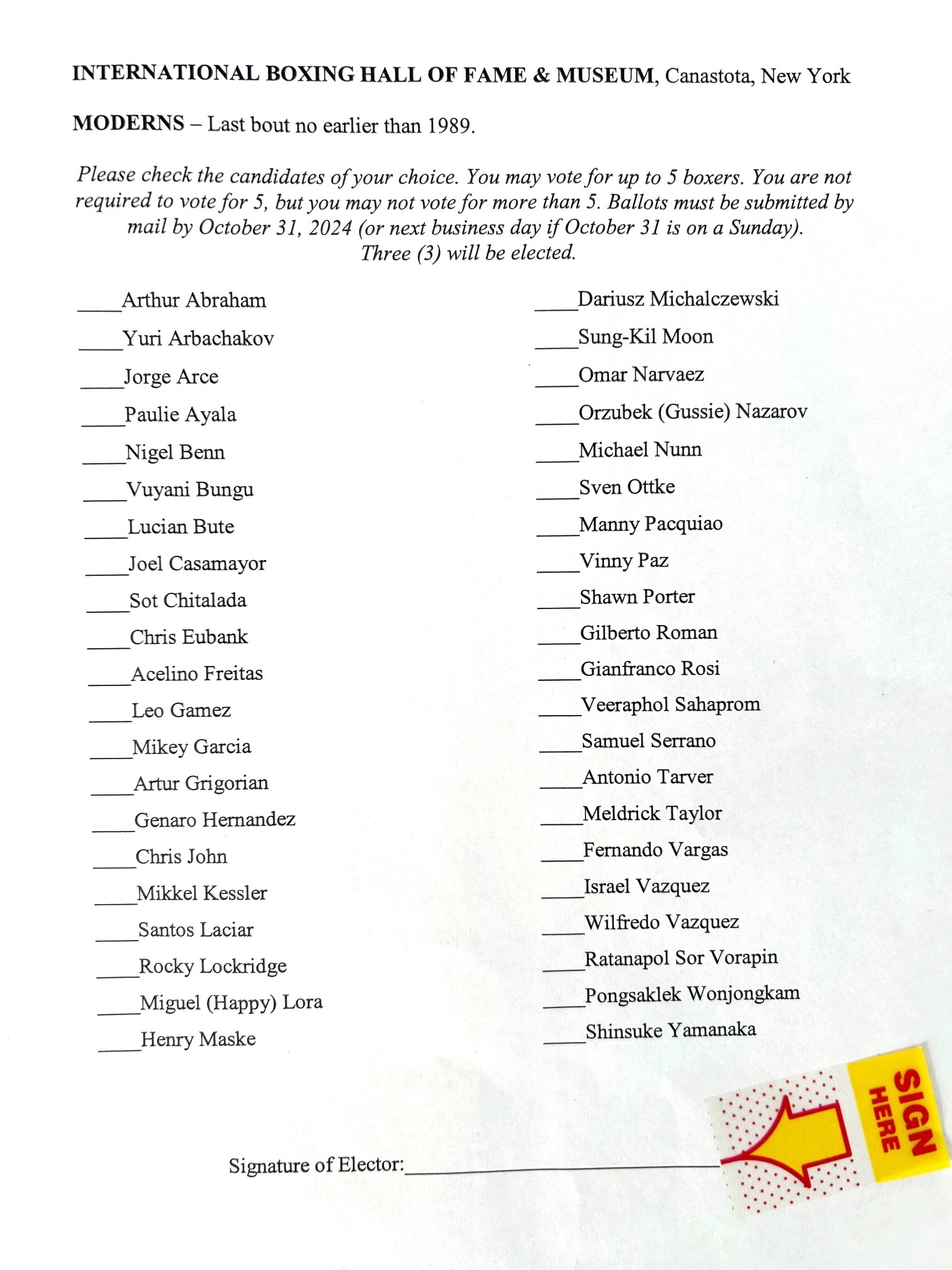

There are seven different categories of inductees, but for this article, in the interest of keeping things under 10,000 words, we’re going to focus mostly on the “Men’s Modern Boxers” category, which honors fighters whose last professional bout took place no earlier than 1989. Here is this year’s ballot:

The previous year’s ballot saw four in this category inducted (it’s usually three, but there was a tie for third place), opening up four spots this year. A boxer becomes eligible for the Hall three years after his final fight, and three of these four ballot openings were filled by newly eligible boxers who last fought in 2021: Pacquiao, Shawn Porter, and Mikey Garcia. The fourth went to Lucian Bute, who’s been retired since 2017 but hadn’t made the ballot yet.

Who determines the new fighters on the ballot? A nominating committee made up of three historians drives the conversation, though input from other experts is solicited and IBHOF Executive Director Ed Brophy has oversight. Don Majeski — New York-based historian, journalist, agent, and matchmaker — was part of that committee since near the very beginning of the IBHOF, alongside Hank Kaplan and Herb Goldman for many years, until Brophy and the Hall decided to make a change a few years ago and bring in a new group.

“You would always start by looking at the pool of boxers who just became eligible for the first time,” Majeski told BoxingScene this week when asked to explain how the committee approached the task. “In the early days, in the 1990s, you would have certain fighters where it was self-evident — when a Marvin Hagler became eligible, or a Sugar Ray Leonard became eligible. But there was a lot more to discuss and debate a level below them. Like, should we put Ken Oberlin or Ceferino Garcia on the ballot? Or, should we put on Billy Soose or Holman Williams?”

BoxingScene reached out to a current member of the screening committee as well, but he considered it a conflict of interest to offer public comments while still actively on that committee. But one can safely assume similar conversations took place as this year’s ballot was being formulated. With Pacquiao, like Hagler or Leonard three decades ago, there was surely nothing to discuss. Bute, Garcia, and Porter presumably emerged from a list many names longer at the conclusion of careful consideration of assorted pros and cons.

But not everyone agrees with those non-Pacquiao selections.

“When I see the guys on this ballot, in the first year of eligibility, I want to throw up,” veteran boxing writer Dan Rafael, formerly of USA Today and ESPN and now authoring the “Fight Freaks Unite” newsletter on Substack, said.

OK, some context for that quote is required.

Rafael has taken issue with the way that, if a boxer doesn’t land on the ballot in their first year or two of eligibility, it’s an uphill climb to ever get on (Bute proving a rare exception this year). Rafael has been stumping for years for 1992 U.S. Olympians Chris Byrd (last fight: 2009) and Vernon Forrest (last fight: 2008), and neither has ever appeared on the ballot, even though their resumes compare favorably to at least some of the nominees. “I’m not saying that these are guys that should be elected,” Rafael noted, “but I think most people would agree at the very least they should get the opportunity to get the up or down vote.”

Rafael said he’s similarly advocated for the likes of Jose Luis Castillo and Marlon Starling, to no avail. Another veteran boxing writer pointed out how hard to fathom it is that Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn have been on the ballot for years but Steve Collins, who went 4-0 against that duo, can’t get a look.

It’s in that context that Rafael’s gag reflex kicked in when he saw Bute, Garcia, and Porter — none of whom he will be voting for this year — had made the cut.

Promoter J Russell Peltz, a 2004 inductee, took it a step further with his feelings about the names on the ballot: “I only voted for Manny Pacquiao,” he said. “You can vote for up to five, but that’s the only one among the moderns that I think deserves to get in.”

Whatever one may think of the new names added to the ballot in a given year, there’s a healthy debate to be had over the fact that, once added to the ballot, there are only two ways to come off of it: getting elected to the Hall, or having the time stamp separating “Modern” from “Old Timer” adjusted such that, based on the date of your final fight, you no longer qualify as Modern.

The Baseball Hall of Fame has rules in place that oust ex-players from the ballot: Anyone who is named on fewer than five per cent of ballots is removed, as is any player who’s been on the ballot 10 times without being elected.

Those rules are designed to prevent nominees with little to no chance of induction from remaining on the ballot in perpetuity. But on the IBHOF ballot, we have fighters like, say, Sven Ottke, who last fought in 2004, who’s been eligible since 2009 (it was a five-year wait after retirement back then), and who may or may not have ever broken five per cent of the vote (numbers are never made public), but whose name still stares back at voters after 15 years.

Rafael believes there should be some rule in place — whether it’s 10 years of trying or something else — that helps refresh the ballot. Majeski feels differently, saying he doesn’t believe one fighter needs to be subtracted in order to add another; he’d rather simply see the ballot expanded to include more nominees.

The more contentious issue, though, is not the number of fighters on the ballot each year, but the number of inductees. Starting in 2006, that number was reduced from four (plus ties) to three (plus ties), a wise adjustment in the eyes of those who felt the Hall was becoming watered down.

But if you compare it to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, where induction is based on reaching a percentage threshold — sometimes resulting in zero new players going in — it remains watered down with the three-fighter guarantee.

“I would like to see them go to a percentage in the modern category,” Majeski said. “If we went to a simple 50 percent at this point, everybody in there would be truly great.

“Look, in any institution, there are going to be different levels. If I say, ‘Name the 100 best fighters in the Hall of Fame,’ the 100th one you name is not going to be as good as the first. Number one is Sugar Ray Robinson, and 100 is, let’s say, Julian Jackson. It’s just the nature of the situation. But you want to draw a line somewhere. If we went to percentages, say 50 per cent, you’re going to always get Pacquiao, you’re going to get Canelo Alvarez, you’re going to always get Mayweather, but you're not going to get anybody who makes you say, ‘Oh, that guy’s mediocre.’”

Rafael also would prefer a percentage-based system. “Maybe baseball’s 75 per cent is too high, so you can make it 70 per cent,” he said. “And I’m not married to that number. But, it stands to reason that there have been years that have gone by, when a class was perceived to be a bit weaker than others, that the fighters elected could be appearing on just 30, 35 percent of the ballots.”

Executive Director Brophy, however, indicates the pro-percentage crowd should not hold its breath.

“There’s nothing in the near future that we’re having a conversation about changing. Three each year, we feel very comfortable with that, it has seemed to work very well,” Brophy said. “That number, we feel it’s proper for the sport. Boxing is international — you’re talking about a large number of boxers to choose from. Some sports are just athletes who compete in the United States. This is international.”

There’s a commonly held belief that the IBHOF, from a business perspective, needs several inductees each year to make sure Induction Weekend attracts visitors. But Brophy refutes that.

“There certainly are funds that are needed to operate a facility like the Hall of Fame, but that has no reflection on the induction process,” Brophy said. “The majority of the needed fundraising is done with different methods apart from the induction weekend. The induction weekend is the celebration. The funding is totally separate and apart from what the purpose of the Hall of Fame is — the purpose is to honor those who have excelled.”

Whatever the methodology for deciding how many fighters get voted in, the system is only as strong as the people casting votes. Peltz sees big flaws on that front — albeit with an emphasis on categories beyond just the Moderns.

“Honestly, you have guys that just don’t know shit,” the promoter, historian, and author of Thirty Dollars and a Cut Eye said. “And because they’re members of the Boxing Writers Association, they get a vote. I mean, if you want to make them eligible for the Moderns, OK, but get them off everything else. Get them off the Observers. Get them off the Non-Participants. Get them off the Old Timers. They vote for their friends, or if they see a name they recognize, they vote for them. It’s just sad.”

Echoed Majeski, succinctly: “If you have to ask who that person is, you shouldn’t be voting in that category.”

In past years, Boxing Writers Association of America members Lee Groves, Cliff Rold, and Springs Toledo tried to alleviate that problem for voters by posting bios of all nominees online. The practice was discontinued, however, leaving it up to voters to do their own research before mailing their ballots back.

It would be nice to think they all take that responsibility seriously and properly explore all options before signing their ballots. It would be nice. Probably a bit naïve, but nice.

Still, the great majority of the voters surely do appreciate the gravity of their responsibility, in part because of their love for boxing and for the Hall of Fame.

“I’m a fan of the Hall of Fame,” Rafael said. “I grew up not that far from the Hall of Fame. I love the institution. And that is why I want to see some changes. Things don’t have to be radically changed. There are just a few things that could be done a little bit differently.”

“People say I’m a hater,” Peltz said. “But it all comes from how much I love boxing. I see who’s getting in today, and it takes something away from what the Hall of Fame is, but I still care about it and love boxing.”

“I think it's the greatest institution we’ve ever had in boxing,” Majeski said. “I think it’s a wonderful thing. The fact that you get so many people with opinions, it shows how much people in the industry really care.”

Eric Raskin is a veteran boxing journalist with more than 25 years of experience covering the sport for such outlets as BoxingScene, ESPN, Grantland, Playboy, Ringside Seat, and The Ring (where he served as managing editor for seven years). He also co-hosted The HBO Boxing Podcast, Showtime Boxing with Raskin & Mulvaney, The Interim Champion Boxing Podcast with Raskin & Mulvaney, and Ring Theory. He has won three first-place writing awards from the BWAA, for his work with The Ring, Grantland, and HBO. Outside boxing, he is the senior editor of CasinoReports and the author of 2014’s The Moneymaker Effect. He can be reached on X or LinkedIn, or via email at RaskinBoxing@yahoo.com.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (7)