The sad news made its way through the boxing community today. Wilbert "Skeeter" McClure has died at age 81.

McClure won a gold medal for the United States in the light-middleweight division at the 1960 Olympics. He turned pro in 1961 and won his first 14 fights. Then he went in tough twice against Luis Rodriguez and lost both times. The most notable entry on his pro ledger is a 1966 draw against Ruben Carter. He retired in 1970 with a 24-8-1 ring record.

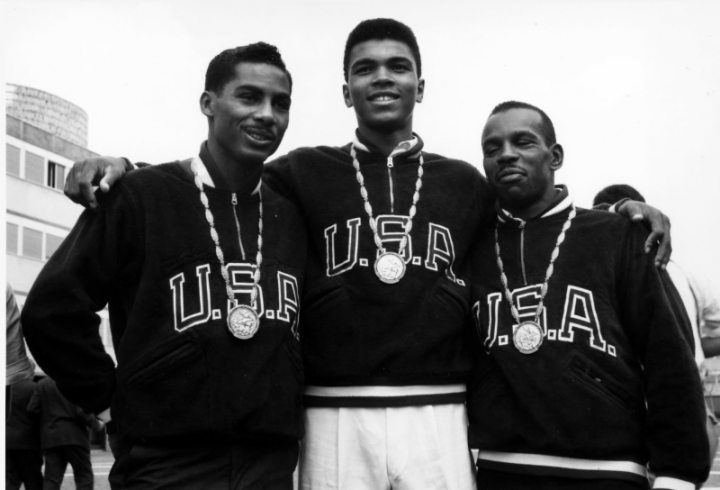

McClure was a remarkable man. After retiring from boxing, he earned a doctorate degree in psychology from Wayne State University and enjoyed a long career as a psychotherapist in Massachusetts. He's also a footnote to history because his roomate at the Rome Olympics was a young man named Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to talk with McClure about his memories of Cassius Clay. His recollections follow:

“I first heard of Cassius Clay back in 1959 at the National Golden Gloves Tournament in Chicago. All the fighters were staying at the same hotel. I was in the lobby and there was this kid there, and I heard him whispering to some other guys, ‘There goes Skeeter McClure.’ That’s because I had won the Nationals in ?58 and was coming back for more. Anyway, he and I both won the Nationals and were part of a team that represented Chicago in an inter-city tournament against New York. We trained together, and I remember Cassius kept bugging everybody on the team, saying, ‘Man, there are all these pretty girls on the streets; all these pretty girls walking around; we got to meet some of these girls.’ And the rest of us weren’t interested in that. We were just there to fight. But he kept agitating and asking and saying, ‘Come on, let’s put on our jackets and go someplace to impress the girls.’

"So finally the coaches set it up. It was all Cassius’s doing. They took us to Marshall High School which was a huge school in Chicago. We had pretty girls as hostesses to show us around. Then we went into the cafeteria for lunch which was filled with more pretty girls. There were pretty girls sitting everywhere. And the guy who’d been agitating just sat there, staring at the food on his tray the whole time. He didn’t say a word. I mean, he was so shy. We teased him about it for days afterward and all he did was look at us and shrug his shoulders. He was very, very shy around girls.

“After that, maybe a month later, the National AAUs were held in my hometown of Toledo. He was there. Both of us won, and I invited him home to meet my parents and brother and sister. And we were together again for the Pan American trials at the University of Wisconsin where he lost to Amos Johnson. Johnson was a grown man, a Marine, and a southpaw. I think that was the last fight he lost until Joe Frazier beat him twelve years later. And what I remember most about that time was, my dad had driven over from Toledo and a bunch of us went out for dinner afterward. We were in this restaurant and Cassius was philosophical. All he said was, ‘I just couldn’t figure him out.’ And if you think about it, when you’re seventeen years old and you meet a man who’s twenty-five or twenty-six, in the service, who fights left-handed, that’s a big disadvantage. But he didn’t grumble or moan or complain. He just said like a champion, ‘I couldn’t figure him out.’

“Then we made the Olympic team together. And in those days, being an Olympian was purely amateur; not like it is now. An amateur was an amateur. In fact, I almost didn’t go to the Olympics because I had one more semester to finish at the University of Toledo. I was paying my own way through college and I didn’t think I’d be able to afford to go to the games and go to school at the same time, until finally the university gave me a scholarship for the last semester so I could afford to go to Rome. Now the money is there to get the talented fighters to where they have to go. A gold medal is seen as a marketing tool. But back then, we weren’t fighting to form the cornerstone of a professional career. We were fighting for pride.

“On the plane going to Rome, I remember, we were trying to decide who would win gold medals, and Cassius led the conversation. He was voluble even then. He was afraid of flying and he talked about that too. But once we got airborne, he managed to distract his fears by talking a lot. He said, ‘Now, I’m gonna win a gold and Skeeter’s gonna win a gold.’ And there was a welterweight who got killed after we came back, Harry Campbell. He said, ‘Campbell’s gonna win a gold.’ And there were two others he predicted, too. We talked about our personalities and boxing styles and how we were nice clean-cut wholesome kids, and we thought that would appeal to the judges.

“In Rome, he was outgoing but he was seriously into boxing. I don’t know of anybody on any team who took it more seriously than he did. We’d walk around and he’d go up to people and shake hands with them, but he had his mind on training. He worked for that gold medal. He trained very, very hard. We all did. You don’t slough off and play games when you’re trying to become an Olympic champion. And certainly, when I watched him train, he was one of the hardest trainers I’d ever seen.

“The boxers all trained together. We ate together. We interacted well as a team. I remember, one night I was in bed - we had three rooms for the boxing team with those awful bunk beds - and I was in my bed writing a love letter to my girl back in the States. Cassius came over and asked what I was writing. I told him, and he asked if I’d write one for him, too. I said, ‘Sure.’ So he told me what to write, and I wrote it out for him and handed him the letter. I don’t know if he copied it over before he sent it back to her or not. But when I wrote it out, he said, ‘Wow, that’s nice.’ He was very pleased. And even though he was a year older than when we’d met in Chicago, he was still very shy around girls. In the ring, he could dance. But at the Olympic Village, we went to one of the Olympic canteens and he didn’t dance at all. And I went to several parties with him later on, and he didn’t dance there either. He just didn’t dance. This was part of that shyness around women. I guess he never learned how to dance and was too shy to go out and do it on his own.

“So that’s the way he was. And looking back - and I believe this; I’ve told Ali this several times - I’ve told him that he was fated. It’s like there was a star when he was born that fated him to do what he was going to do and to have impact on mankind around the globe, and there’s nothing he could have done to prevent it and nothing he could have done to make it happen. It’s just one of those things. You know, psychology is a science, but there’s some slippage in there. There’s still some philosophy, and we’re still trying to understand and explain human behavior, and some things we just can’t explain. And when you think about this young man’s life - when I first saw him when he came to our home in Toledo, his pants were up at his ankles, his sports coat was too short, but it’s like the clothing was irrelevant because he glowed. Even then, you knew he was special; a nice, bright, warm, wonderful person. That was thirty years ago. And I guess if someone had told me back then that Cassius Clay would become the most famous person in the world, I never would have believed them. It just didn’t seem possible, but look at him now.”

So thank you to Wilbert "Skeeter" McClure for being who he was and also for adding a page to the history of Muhammad Ali.

ADD COMMENT