When one considers how exciting boxing is, how easy it is to follow even with only a rudimentary understanding of what it takes to win a fight, and the incredible characters involved who shape the drama, it’s frustrating that the sport isn’t (universally) regarded as one of the biggest on the planet.

Some will argue that it is, particularly after the exceptional opening six months of 2024. But only those promoting their own businesses from inside of the boxing bubble, and thus enjoying something of a lucrative period, are making those claims with any validity. Outside of that bubble, where the widespread public’s interest is generally pricked only once or twice a year, the view is somewhat different.

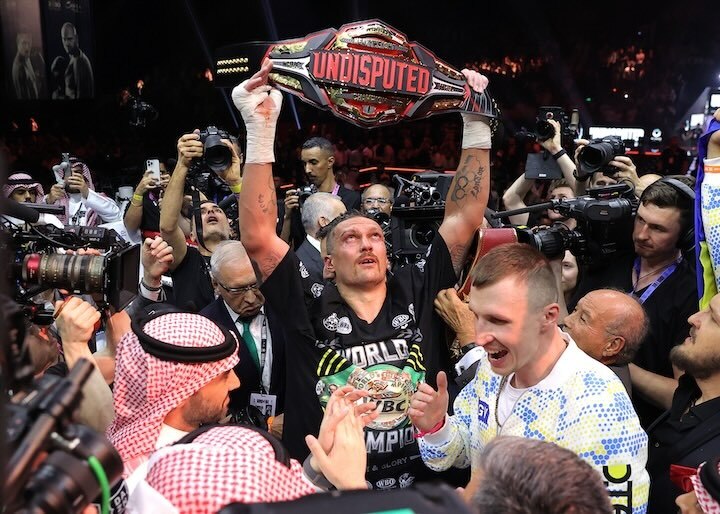

Notwithstanding colossal events like Tyson Fury-Oleksandr Usyk, boxing simply doesn’t move the dial frequently enough. It’s a sport known for having the occasional big fight but who, besides the likes of you and me, is taking notice of the thousands of other fights often enough for the sport to become a household staple?

The lack of interest can in large part be explained by a longstanding, albeit understandable, reluctance to turn boxing into a structured enterprise. After all, this is not a team sport, nor has it ever been a slave to the clock, the calendar year or a fixture list, and thus the tried and tested format of mainstream sports – the kind that ensure league competitions, cups and tournaments are easily digestible at set times and on certain dates – simply does not exist here.

Though it guarantees extra interest when the showstopping fights are suddenly made – simply because they occur so rarely – the more familiar chaos often prohibits the making of the best fights and though the inane number of belts on offer might indeed mean a greater occurrence of ‘world title’ fights, it only creates confusion for the general sports fan. If you disagree, go and tell one of the million or so who bought into the hoopla surrounding Fury-Usyk that Daniel Dubois is now a world heavyweight champion and watch their eyes glaze over as you attempt to explain why, barely two months later, there is no longer an undisputed king.

In recent months, thanks almost exclusively to the involvement of Saudi Arabia’s General Entertainment Authority – headed by Turki Alalshikh – the number of competitive fights at elite level has risen sharply. So, too, the unification of titles. It’s a welcome trend. As boxing goes, there can be little argument that it’s in a good place so it may appear a little churlish to criticize here, particularly with further plans from Alalshikh at advanced stages.

But is the sport really healing, or has a gigantic silk plaster merely been placed on old wounds? After all, it will take more than sporadic injections of cash from the Middle East for the changes to be permanent, for any improvements to be widespread, and for the implementation of them sustainable in the long term. Further – though we can dress the windows with lavish, eye-catching contests, it’s also just as important to ensure that the rest of the shop is well stocked and being managed correctly for the business to really prosper.

Here are six points that boxing needs to address to really become a leading sport.

- ONE WORLD CHAMPION PER DIVISION

There are four sanctioning bodies (WBC, WBA, IBF, WBO) recognized in the sport – five, if you include the IBO. All have different rankings, and none have any controlling body, aside from the Association of Boxing Commissions (ABC), to whom they must answer.

So, and bear with me here, the champion of one organization cannot be ranked by the other organizations, and therefore there is not a single rule, commission or sanctioning body in place that demands that the best take on the best.

The rules of the WBC, arguably the most influential of all rankings organizations, state: ‘No champion from another boxing organization will be classified within the top 10, since their boxing obligations do not allow them to fight for a WBC title, and therefore such opportunities will be granted to those fighters who are willing to fight for a WBC championship.’ No sport could thrive under such ludicrous circumstances.

Though seasoned boxing fans have begrudgingly accepted this system, studied the conflicting rankings and lost their minds at the sheer lunacy of it all, it is exceptionally difficult to explain to those with only a passing interest why certain weight classes might feature five or more ‘world’ champions.

Frequently, several world-title fights from the same division occur within a short timeframe, sometimes even on the same bill, all featuring different boxers, with each belt-holder introduced to the crowd – via a straight face – as the world champion. A case in point would be the three-week period in 2020 between October 17 and November 7 when Teofimo Lopez, Gervonta Davis and Devin Haney all paraded versions of the world lightweight title. Imagine, for a moment, you were new to the sport, had thoroughly enjoyed Lopez defeating Vasiliy Lomachenko and invested in the story of him being the new 135-pound supremo, and were then presented with not one but two more who supposedly also rule the world at lightweight mere days later.

Although Dubois-Anthony Joshua is a tremendous matchup at heavyweight and was likely finalized at the negotiating table thanks to an IBF strap being involved, are we really going to try and dress it up as a world-title fight barely five months after we all went gaga over an undisputed champion being crowned for the first time in 25 years? Those at the heart of the promotion may believe an IBF title adds extra lustre to the contest. The truth is, Dubois-Joshua sells big – with or without the red leather belt.

The bottom line is the existing championship system is too convoluted to understand, and if the public at large can’t understand it and in turn invest their time and money into something, that something will struggle to grow. Very simply, the sport of boxing should have a championship system that is as easy to follow as the fights themselves.

One world champion per division would erase that confusion and in turn make our sport an inviting one – not only for fans but also the widespread media who, aside from specialized outlets, are only aware that boxing exists when a truly massive fight occurs.

So how did we get into this mess? The proliferation of titles is appealing to both promoters and broadcasters because they can dress up more fights as ‘world-title’ fights. Some have argued that one champion would restrict the opportunities for the contenders and there’s some truth in that. But do other sports suffer because only a select few get to win the ultimate prize?

That so many title fights go by unnoticed outside of the boxing bubble illustrates that all the extra belts do is dilute both interest and quality. And it’s not just the fault of promoters, broadcasters and sanctioning bodies – the belts are now so ingrained in the entire sport’s consciousness that changing the system will take a monumental effort from the entire industry.

Is there a solution? With four (or five) sanctioning bodies in place, perhaps just recognizing one of them would help. For that to happen, however, the one left standing would need to address their current policies – on rankings, sanctioning fees, cosy relationships with certain powerbrokers and their attitude to performance enhancing drugs – to really stand out from the crowd. And though there are better organizations than others, expecting one to rise and the others to fall is unrealistic.

There have frequently been murmurs that a superpower – i.e. Saudi Arabia or even Dana White – might buy all the bodies in an effort to gain complete control. But then what?

A more sensible solution would appear to be the creation of a superior system – one that in time would make the old one completely irrelevant. “That will never happen,” everyone groans. But why not? If half-a-billion can be spent on one event – which was reportedly the fee to stage Fury-Francis Ngannou last year – then surely there’s money available to overhaul a broken system?

By creating a title that only the best fighters can contest would go some way to winning fans over quickly. And being the definitive best fighter in the world would appeal greatly to the ego and competitive spirit of the leading boxers – particularly if there is a clear path to that status. Elimination bouts would become huge events – think quarter and semi-finals of major tournaments – and ruling that championships must be contested three times a year would ensure regular top-notch action.

Attaching extra prize money to winning and defending the title – as opposed to the sanctioning fees that boxers wishing to fight for the alphabet titles are currently obliged to pay – would sweeten the process, too.

Part II (of VI) will be published tomorrow (July 10).

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (25)