I’ve grown a bit as a boxing fan since March 8, 1971.

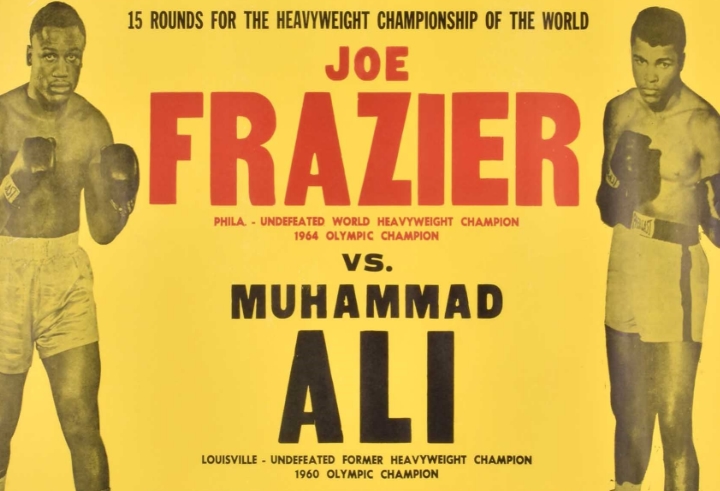

When fight night arrived back then, neither Muhammad Ali nor Joe Frazier was even on my radar.

Cake and ice cream? Yes.

Style nuances and competitive contrasts? Not so much.

OK. Perhaps I should clarify that the fight occurred three days after I turned 2 years old.

So suffice to say I had other priorities.

That being said, it’s been a fascinating touchstone for subsequent decades – considering the individual achievements of its principals and the monumental impact of their career-long rivalry.

Many events have come and gone in half a century.

A few will be recalled past the lifetimes of those involved.

But to anyone who was around in 1971, none have challenged “The Greatest” vs. “Smokin’ Joe.”

“It’s not even close. Doesn’t even register,” Hank Goldberg, best known for his ‘Hammerin’ Hank’ persona on ESPN, told me during the run-up to Mayweather-Pacquiao in 2015 – when I asked him how that match, the prospect of which had held fight fans hostage for years, measured up to Ali-Frazier I.

He was 23 in March 1971.

“As big as (Mayweather-Pacquiao) seems, it’s not even a fraction of the interest – to say nothing of the significance – as that fight had. It’s hard to compare the two because they’re on such different levels.”

Where the latter galvanized a base consumed with superficiality, the former was the real deal.

“May-Pac had very little sociopolitical significance,” said Jim Lampley, who shared announce team duties for that fight’s unique HBO/Showtime joint broadcast. “The selfie fight, a platform for spectators to make a social media splash, underlining its genuinely trivial value compared to Ali-Frazier.”

Lampley was a month away from turning 22 when Ali-Frazier I went down.

“If Ali-Frazier I was a 100, maybe Holmes-Cooney was a 60,” he said.

“From an American society standpoint, I can't even think of anything else to discuss. Holmes-Ali maybe. Mick Jagger called that ‘the end of our youth.’ Best line of boxing commentary ever.”

Holmes-Cooney, fought 11 years later in 1982, was culturally polarizing thanks largely to the promotional stylings of Don King and Dennis Rappaport, who reaped interest by sowing racial tensions.

Cooney, a comparatively unproven white contender, was paid equal money and given a significant amount of pre-fight attention compared to Holmes, a black champion who’d not lost in 39 fights and had won the championship and defended it 11 times from 1978 to 1982.

The challenger was on the cover of both Sports Illustrated and Time before the fight, and, despite Holmes’ status as champion, was introduced second once the fighters reached the ring in Las Vegas.

Holmes, though, controlled most of the fight, scored two knockdowns and won by TKO in Round 13.

“The most socially powerful blend of boxing competition,” Lampley said, “and its surrounding worlds.”

Among the other also-rans, Holmes’ fight with Ali occurred 20 months before he faced Cooney and was momentous not for the competition – Holmes dominated before Ali’s corner finally gave him up after 10 rounds – but for the symbolic torch-passing from the Ali circus to Holmes’ lunch-pail persona.

An unneeded transition, given that Ali had retired as champion two years earlier and might have stayed gone – and perhaps had a cleaner bill of health – had King not made him an $8 million offer.

“All the other fights pushed him to the edge. This one buried him,” Ferdie Pacheco said on an ESPN documentary, Muhammad and Larry, in 2009. “It shouldn’t have been. He should’ve had a nice, normal life – to 80, 90, 100 – Ali could have lived forever. He was so strong. But we didn’t get to see it.”

As for a fight that’ll equal Ali-Frazier, Lampley insists, we won’t get to see that either.

“It’s a relic,” he said. “Because sociopolitical ideas are not treated to the same general approval as was the case then. The moral landscape was defined by a less populist bent, and values which were revered then are disdained now. Mayweather vs. Pacquaio was truly the defining event of the current ethos.

“And no fighter is Muhammad Ali.”

* * * * * * * * * *

This week’s title-fight schedule:

WBA/WBC super flyweight titles – Dallas, Texas

Roman Gonzalez (WBA champ/No. 3 Ring) vs. Juan Francisco Estrada (WBC champ/No. 1 Ring)

Gonzalez (50-2, 41 KO): Second title defense; Four-fight win streak since lone career losses (4-0, 3 KO)

Estrada (41-3, 28 KO): Third title defense; Lost to Gonzalez (UD 12) in title fight at 108 pounds in 2012

Fitzbitz says: There was a noticeable gap between the two when Gonzalez was viewed as the world’s top fighter. He’s not anymore. There’s still a gap now, but in the other direction. Estrada by decision (85/15)

WBA light flyweight title – Dallas, Texas

Hiroto Kyoguchi (champion/No. 1 Ring) vs. Axel Aragon Vega (No. 10 WBA/Unranked Ring)

Kyoguchi (14-0, 9 KO): Third title defense; Held IBF title at 105 pounds (2017-18, two defenses)

Vega (14-3-1, 8 KO): Second title fight (0-1); Lost WBO title fight at 105 pounds in 2019) (TD 7)

Fitzbitz says: Kyoguchi is one of a wave of prodigious Asians who’ve won titles early in their careers. He’s sure to impress against a guy with two wins over plus-.500 foes. Ahh, the WBA. Kyoguchi in 6 (99/1)

Last week's picks: None

2021 picks record: 4-2 (66.7 percent)

Overall picks record: 1,160-377 (75.5 percent)

NOTE: Fights previewed are only those involving a sanctioning body's full-fledged title-holder – no interim, diamond, silver, etc. Fights for WBA "world championships" are only included if no "super champion" exists in the weight class.

Lyle Fitzsimmons has covered professional boxing since 1995 and written a weekly column for Boxing Scene since 2008. He is a full voting member of the Boxing Writers Association of America. Reach him at fitzbitz@msn.com or follow him on Twitter – @fitzbitz.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (13)