Callum Walsh has only been a professional prizefighter for two-and-a-quarter years, enough time to log 10 wins from 10 fights. A quick glance at his boxing record reveals something else apart from the victories and KOs: he means to make St. Patrick’s Day his, in the same way that Oscar De La Hoya and Canelo Alvarez sought to capture the Cinco de Mayo and Mexican Independence Day weekends.

Fully 30 per cent of Walsh’s pro bouts have been fought on or as near as possible to March 17: his second outing, a first-round stoppage of Gael Ibarra in 2022; his sixth, a second-round TKO of Wesley Tucker last year; and Friday’s win over Dauren Yeleussinov.

St. Patrick’s Day doesn’t have the same cachet in a pugilistic sense of either of the Mexican holidays, perhaps partly because Ireland no longer has quite the grip on the sweet science that its emigres did in the first part of the 20th century, and perhaps also because there is a disconnect between the holiday as understood and experienced by the Irish and the boozefest it has descended into in the colonies.

That said, March 17 and thereabouts has some proud moments of which to boast in boxing history. Rocky Marciano made his professional debut on that day in 1947, although one suspects the timing was coincidental. Exactly 70 years later, and with greater intention, Michael Conlan took his professional bow at the Theater at Madison Square Garden. Steve Collins defeated Chris Eubank and took his super middleweight title on the same day in 1995.

Fighting on St. Patrick’s Day didn’t help Jem Roche, who took on Tommy Burns for the heavyweight championship in 1908 at the Theatre Royal in Dublin and was knocked out in 88 seconds. Fifteen years later, however, County Clare’s Mike McTigue challenged Battling Siki for the light heavyweight crown at the La Scala Theatre, also in Dublin, and emerged with the championship via a closely contested 20 round decision.

What made the occasion all the more memorable was that the bout took place in the midst of another battle: the Irish Civil War, which had flared up in the summer of 1922 following the end of Ireland’s war of independence from Britain and was two months away from its own conclusion.

Perhaps the most famous fight to fall on St. Patrick’s Day, however, didn’t take place in Ireland or involve any Irish boxers – although one of the combatants, James J. Corbett, was the son of a man from County Mayo.

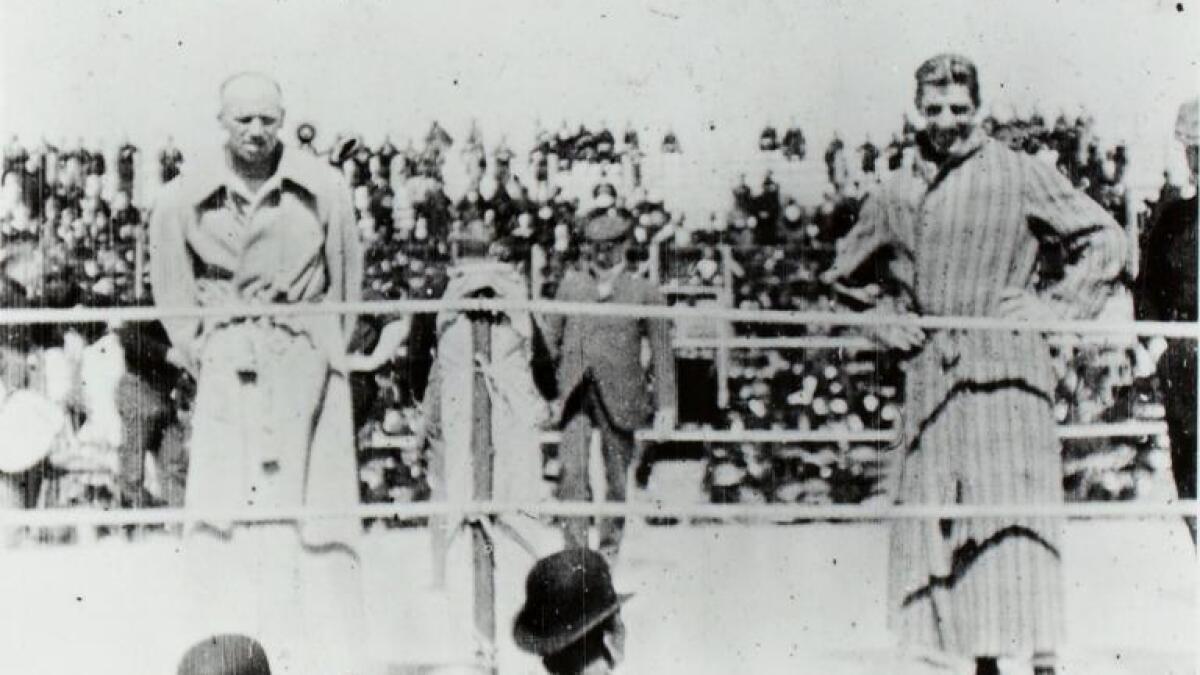

On March 17, 1897, Corbett squared off against Bob Fitzsimmons in Carson City, Nevada in defense of the heavyweight championship he had annexed from John L. Sullivan five years previously. Corbett was neither an active fighter nor a busy champion; although records from that era are often incomplete or contradictory, the International Boxing Hall of Fame (of which Corbett was a founding inductee) lists him as compiling a record of just 11-4-3 over the course of his career. He had made just one official defense of his heavyweight crown since defeating Sullivan by 21st round knockout, erasing Charlie Mitchell inside three frames in 1894. His absenteeism had led to Fitzsimmons’ December 1896 fight with Tom Sharkey – which saw the former disqualified, amid much controversy, by referee Wyatt Earp – advertised as being for the crown. But, having beaten Sullivan, Corbett was the archetypal “man who beat the man” and if Fitzsimmons wanted to become truly recognized as the king, he had to get past him first.

Corbett was a pioneer in the true sense of the word. At a time when much boxing was short on refinement and big on bullrushes, Corbett was a true technician, who underwent strict training for his bouts and who executed feints, movement, and jabs when he was in the ring.

Fitzsimmons, meanwhile, was born in Cornwall, England before emigrating first to New Zealand and then Australia and ultimately the United States. He had won the middleweight title in 1891 by knocking out one of Ireland’s greatest, ‘Nonpareil’ Jack Dempsey before ultimately stepping up to heavyweight – the light-heavyweight division having not yet been created. A noted body-puncher, he had dropped Sharkey, seemingly for the count, with his patented “solar plexus punch,” only for Earp to rule a low blow and issue his disqualification; against Corbett, however, Fitzsimmons made no mistake.

Corbett started by far the stronger of the two and dropped Fitzsimmons in round six. But Fitzsimmons rallied, strafing Corbett to the body and slowing him down, before poleaxing him with his solar plexus shot in the fourteenth.

The fight was recorded on film, and the resulting documentary – called, simply, The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight – was released to much acclaim. Clocking in at around 100 minutes, it was the longest movie yet released, and indeed has been dubbed not just the first feature film on sports, but the first true feature film, period.

At the time, boxing was banned in 21 states in the union, and for all the praise and attention it received, the documentary also met its fair share of disapproval, not least from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which sought to outlaw the film by prohibiting it from being sent by mail. The particular cause of their agita was the fact that, while women were largely prohibited from attending live boxing, there were no such restrictions on them viewing the movie. That worked to the advantage of the handsome Corbett who, despite losing the fight, became the sports world’s first true sex symbol, and who transitioned seamlessly from pugilism to acting.

Fitzsimmons would make just one successful defense of his crown, against Lew Joslin, before losing it by knockout to James Jeffries in 1899. Jeffries held the crown for five years, retiring to his alfalfa farm in 1904 with an unbeaten record, before being lured out of retirement as “The Great White Hope” in a failed attempt to reclaim the crown from Jack Johnson – on, as it happened, another holiday: July 4, 1910.

The full print of The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight no longer exists, but the movie was entered into the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress as a “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant film.”

ADD COMMENT