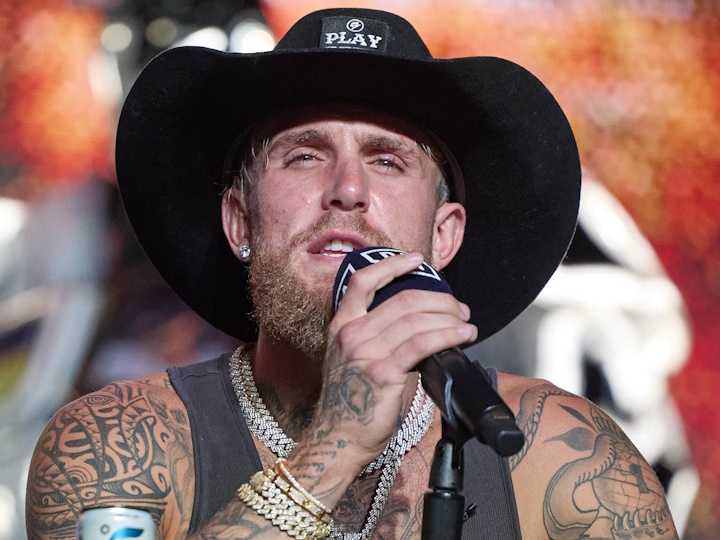

Both Jake Paul and his brother Logan Paul had appearances on pay-per-view on Saturday night. As Jake was arriving at the American Airlines Center in Dallas, TX in an actual tank ahead of his boxing match against UFC legend Nate Diaz, Logan was wrestling in the opening match of WWE Summerslam in Detroit, MI against Ricochet.

Though one was obviously an actual fight and the other a predetermined performance, there were plenty of similarities between the two, as if they were borrowing storylines from one another to promote their respective events. Jake was once again boxing an MMA star, oscillating between dangling the possibility of danger because he was facing a more experienced combat athlete and laughing at those who gobbled up the bait on the lure. In pro wrestling storyline, Logan faced an experienced wrestler and sneered that despite being a relative novice, he was both more famous and able to beat him. The crowd at both events was strongly rooting against the Paul brothers, as they played up the fact that they were frustratingly successful interlopers in their respective new fields.

After Logan defeated Ricochet, he hopped on a private jet, still in his wrestling gear, to be ringside to support Jake in a fight that while obviously not predetermined, was as carefully—and one might say brilliantly—curated as a pro wrestling match.

As he has several times already in his pro boxing career, the younger Paul brother preyed upon the reputation of an MMA fighter known for his stand-up abilities in the octagon. Despite it being demonstrated many times in the past—several times by him--that specialists will almost always defeat multi-disciplinary fighter, more than enough people felt that Diaz might be an exception to the rule to make the fight sellable. Although Diaz’s primary talents lie are Brazilian jiu-jitsu, there always existed the mythology that he was a professional caliber boxer in hiding and that his wide sampling of combat disciplines simply drew him to the octagon instead. In particular, a decade-plus-old tale that he sparred with Andre Ward, who was kind in his assessment of Diaz afterwards, was propped up as proof of his pugilistic prowess.

From a promotional perspective, Paul is and was battling a marketing fatigue in terms of boxing MMA fighters, as more and more observers are becoming hip to the realities of the situation and the clever illusion being pulled. But Diaz was the perfect choice of opponent marketing-wise, particularly after Paul’s first loss to Tommy Fury earlier this year. Diaz presented only mildly more of a threat than Paul’s opponents other than Fury, but carried with him the aforementioned reputation that he was the outlier in terms of MMA fighters-turned-boxers. Maybe more importantly though, Diaz’s fans who mostly populated the arena on Saturday night, didn’t seem to care whether they were wrong or right, whether he won or not, so long as Diaz played the hits and clowned around throughout the fight. Both Diaz himself and some of his supporters essentially admitted as much before and after the bout, hedging their bets with messaging like “if this were a real fight we know how this would go,” and “if this were a fight to the death Diaz would win.”

“Real fight” was of course code for “MMA bout,” and “fight to the death” for “street fight,” but of course this was neither of those things. It was a boxing match, one Diaz demonstrated early on he had no chance of winning. Diaz’s patented slapping punch delivery quite simply did not translate to a pro boxing ring, rendering him unable to land at long range whatsoever. On the inside, Diaz was able to hustle and scuff Paul with a few shots here and there, but primarily Diaz spent time absorbing blows from Paul, taunting him, feigning being hurt and pandering to an adoring crowd for whom their hero’s ability to take the punishment and still laugh was satisfying enough.

In some ways, that was more than enough to satisfy everybody who watched the bout with actual interest rather than disdain. Diaz essentially told the tale that he was able to strut into a boxing ring and take Paul’s best shots without caring too much, but that the circumstances would (obviously) be different in an MMA bout. Diaz even applied some half-hearted guillotine chokes, including one in the final moments of the bout, to make allusions to this. Otherwise, he was game for ten rounds, engaging with the crowd, and provided Paul with another victory and added credibility in the process. In other words, the perfect opponent.

Diaz’s brand of comedic nonchalance in the face of losing was interesting to behold in the ring with Paul, because it was precisely the type of fight some observers wanted Paul to participate in earlier in his career. When Paul launched his boxing career and faced a pro basketball player and other MMA fighters, there were calls from purists for him to have taken a more traditional route. In particular, there were taunts that journeymen would have beaten Paul, and that he would have been better off facing them and learning in those types of bouts instead.

Paul’s reasoning for not going that route is obvious by now—he is very famous and very popular, but Jake Paul vs. someone without built-in clout wouldn’t have been particularly interesting to the general audience or sports media at that stage in his career, and perhaps not even now. No matter how serious Paul’s intentions of glory are, he is a brand and a capitalist first, and that will always color the matchmaking decisions he makes. But the irony is that the reality of how true journeymen operate, specifically those in the United Kingdom and Europe, is not all that dissimilar to how Diaz conducted himself on Saturday. There is the tacit understanding that while journeymen are not explicitly throwing a fight, it’s in their best interests to not win, but to simply give honest work yet minimal danger to the home fighter. Diaz didn’t have this understanding, but his approach mimicked how many journeymen behave. Names like Lewis van Poetsch, Tony Booth, Jevgenijs Andrejevs and many more over the years have mastered the art of putting on an amusing show in a losing effort in service of the sport—it’s how they acquire regular work. They joke around, they posture, they talk to the audience at times, explode with a little bit of good work then return to focusing on defense. Most journeymen are better boxers than Diaz, and sometimes even better than the fighters they’re tasked with losing to, but the result Diaz produced for Paul was similar nonetheless. The only difference is that Diaz probably expected to win—even if he wasn’t particularly bothered when he didn’t.

Could some true journeyman in the world trouble Paul, or teach him some lessons that Diaz couldn’t? Of course. That’s not a slight on Paul but the realities of the journeymen profession and their true skill level. In fact, the same could be said for plenty of more experienced, better schooled fighters than Paul. But Paul isn’t going to and doesn’t need to go that route. And if he did, he would be treated the way any other locally popular A-side booked against a journeyman would be: The opponent would be pesky and competitive enough to help him learn without screwing up the money, of which Paul brings plenty to the table, more than most elite fighters do, let alone prospects.

Nonetheless, as a journeyman would have done, Diaz was durable enough to take Paul ten rounds for the first time in his career, kept the crowd amused, and helped show what Paul’s limitations still are at this stage in his career. Paul doesn’t have magic eraser power at cruiserweight relative to the field—he’s gone the distance in half of his fights—and when his competition improves as Paul looks to fulfill his promise of becoming world champion by 2026, he will have to be able to continue winning fights against fighters he can’t hurt, but can hurt him, using boxing ability and movement.

On this night though, there was only the illusion of danger, the outcome was never actually in doubt. A little pro wrestling, a little pro boxing.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (3)