It’s pretty amazing to think about.

Seems as soon as one high-profile championship fight anniversary from the late 1970s or early 1980s passes, another one comes rolling through within a week or two.

So when people refer to that stretch as one of boxing’s golden ages, it’s not exactly hyperbolic.

Case in point, two weeks ago Wednesday was the 39th anniversary of the most significant title match of my lifetime – the classic welterweight “Showdown” between Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns.

It was the fight that I wrote about as a seventh-grade English student, and it was my teacher’s reaction to that piece that kick-started my desire to pursue the career I’ve enjoyed every moment of since.

And this past Sunday, it was exactly 40 years since Marvin Hagler dethroned Alan Minter for the middleweight crown amid a shower of bottles and cans at Wembley Arena in London.

Of course, that date was a tad melancholy this year after Minter died earlier this month at age 69.

But this week’s piece of 40th anniversary cake won’t go down quite so smoothly.

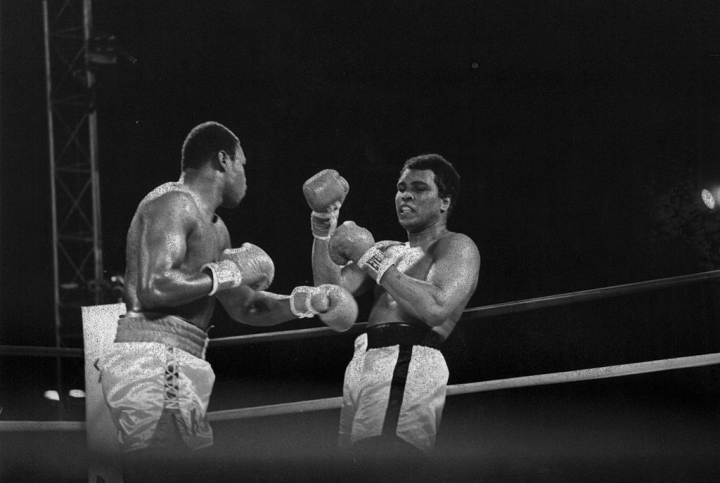

When Friday, Oct. 2 arrives it’ll be precisely four decades since the most heartbreaking and avoidable result of my lifetime, the WBC heavyweight title match between Larry Holmes and Muhammad Ali.

Forty years since the beating Ali need never have taken.

That night in Las Vegas -- with television cameras extending front-row seating far beyond the Nevada desert -- nothing less than a crime was committed against the best heavyweight who ever lived.

The three-time champ met a devastating Waterloo at Caesars Palace -- taking a 10-round bludgeoning from a prime Holmes in an ill-advised try for reign No. 4 as the division's best fighter.

He lost a sleepwalk with Trevor Berbick 14 months later, but some believe the beating suffered against Holmes was hugely responsible for worsening Ali’s post-Manila struggles.

Nevertheless, an authority as respected as Sports Illustrated’s Pat Putnam was duped, penning these words for a Sept. 29, 1980 issue whose cover displayed a taut, sneering, doomed challenger:

“Once this figured to be the fight no one would want to see: Ali, flabby and floundering, would be stung into submission by the flashing jab of a man eight years younger; he would inevitably be hammered onto the canvas by a boxer who had 27 knockouts in 35 fights. It would be no more than a grotesque replay of the 28-year-old Rocky Marciano vs. the 37-year-old Joe Louis, of the tough young fighter against the venerated but vulnerable former champion whose comeback could end in nothing but the sad tolling of nine-ten-and-out.

“It won’t happen that way.”

An ESPN documentary a few years back shed light on Ali’s condition as the fight approached -- with several members of his entourage admitting he'd shown decline long before reaching the ring.

Given that he hadn't fought in the preceding two years, wasn’t at normal lucidity in training camp and had gotten a dubious bill of health from a pre-licensing Mayo Clinic exam, there's zero excuse for Holmes having landed anything more than a fight-night handshake.

Ali’s management shouldn't have signed it. The commission shouldn't have sanctioned it.

And when push came to shove, trusted advisers like Angelo Dundee -- who spent three decades before his own death professing unwavering care for the man -- should have stopped it before it started.

No reasons offered before, during or since hold water.

Dundee's claim he didn't have Ali's ear rings hollow, and the concession of Gene Kilroy that the fighter confided something "wasn't right" in advance puts the business manager next in line as an accomplice.

As hard-headed as Ali might have been, it makes no difference.

As much money as was offered or as many bets Nevada stood to gain, so what?

As difficult as it would have been to stop it before it started, doesn't matter.

The job descriptions of Dundee, Kilroy, Wali Muhammad and others included a mandate to prepare their man for battle, not just revel in his glow. And in a scenario where nearly everyone believed success was impossible, their obligation was to keep him safe from a beating that could leave permanent scars.

If Dundee had walked away, along with anyone else who'd smelled what was up, the legs would have been taken from under the event. And maybe it would have helped.

But no one did. No one had the courage to call it what it was -- an atrocity.

And by staying, they're all complicit with what unfolded.

So we're left with Howard Cosell's naïve bellowing when it finally was waved off, insisting Dundee "cared too much" to let the beating continue to round 11.

Sure.

It took 10 rounds to realize a swollen-faced Ali had no chance? Dundee had to see him beaten like a heavy bag for a full 30 minutes, when anyone else saw far sooner that victory was no option?

Nonsense. Plain and simple.

History now shows the depth of the scars caused.

And it also shows that every team member failed miserably.

With each interview they’ve given or autobiography they've written -- recalling anecdotes from life with a 220-pound traveling circus -- a layer of hypocrisy is added to a story that should’ve ended better.

Ali should have been the one making the memoirs tour, throwing flurries for pay-per-view introductions and being the best possible ambassador for a sport badly needing one.

Instead he dwindled to sympathetic figurehead and became a symbol of brutality for the abolitionist crowd. Meanwhile, his ex-caretakers present vacant rationale and promote their latest books.

His death left a void it’ll take 100 men to fill.

And when still-healthy subordinates return for a second helping of nostalgia pie, their slices should be accompanied by a note saying, “Eat well, it didn't have to be this way.”

Though Joe Frazier, Ken Norton and George Foreman rendered many worse for wear, the Ali who danced rings around Leon Spinks in September 1978 was far healthier than the one who turned from Holmes two years later but stubbornly refused to fall.

Too brave and too sturdy for his own good.

And too good a man to have so tragic a final chapter, no matter the inconvenience.

Shame on those who let it happen.

* * * * * * * * * *

This week’s title-fight schedule:

No title fights scheduled.

Last week's picks: 6-0 (WIN: Briedis, Taylor, Charlo, Nery, Charlo, Casimero)

2020 picks record: 24-3 (88.9 percent)

Overall picks record: 1,141-368 (75.6 percent)

NOTE: Fights previewed are only those involving a sanctioning body's full-fledged title-holder – no interim, diamond, silver, etc. Fights for WBA "world championships" are only included if no "super champion" exists in the weight class.

Lyle Fitzsimmons has covered professional boxing since 1995 and written a weekly column for Boxing Scene since 2008. He is a full voting member of the Boxing Writers Association of America. Reach him at fitzbitz@msn.com or follow him on Twitter – @fitzbitz.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (7)