Though we’ve all rightly bemoaned the amount of time it’s taken to get here while blaming the multiple sanctioning bodies, the promoters, the broadcasters and even the various fighters involved for the delay, the truth is that contests as ginormous as Tyson Fury-Oleksandr Usyk have always been something of a rarity.

The existing politicking and convoluted championship system should be held at least partly responsible, however. In practically every other era (aside from this four-belt era), the champion would fight their closest rival as a matter of course. Consequently, there simply wasn’t enough time – like, say, 25 years – for the desire to build like it has for this one. Thus, if we’re to draw a positive from that quarter of a century wait, it’s that we wouldn’t now be nearly as excited if we hadn’t been forced to endure it.

But there are other fights to which we can compare Fury-Usyk, at least in terms of interest.

When Jack Johnson was the world heavyweight champion, such was the way of the world in 1910 there was an almighty clamour for him to lose his championship to a white man. So much so that former champion – the unbeaten but ageing James J Jeffries – was hauled out of a six-year retirement weighing a reported 300lbs with a $10,000 signing on bonus and the promise of a hefty portion of the $101,000 purse.

Legend has it that Johnson initially agreed to throw the fight for a handsome sum but when the location was switched from San Francisco to Reno, and thus the original contract was ripped up, the champion had a change of heart and declared it would be a case of best man wins.

Show promoter Tex Rickard – who hailed Johnson-Jeffries as the ‘Fight of the Century’ – was also doubling up as the referee and several observers from the time reported that, privately, Jeffries knew the only way he could win was if the fix was in.

Regardless, the public was invested to extreme levels and an arena was constructed specifically for the fight, which took place on July 4, 1910. Jeffries, even though out of shape and ambition, opened as a 10/7 favourite and nearly all the 15,670 in attendance expected him to win. In Chicago a further 10,000 people, who like those in the arena were almost exclusively white, gathered outside the Tribune building to listen to a bloke with a megaphone provide updates on the action. In New York, 30,000 were in Times Square to keep their eyes on a new device that provided automated updates.

The fight itself was a one-sided and tepid affair. In the 15th round, Johnson decked a bloated and bloody Jeffries who dutifully albeit hopelessly clambered to his feet. Count beaten but Johnson far from, Jeffries then found himself jabbed out of the ring, helped back in by reporters, then finally floored for the third and final time. The bludgeoning was all over, so too was the notion of Johnson-Jeffries ever being a good idea.

Twenty-eight years later, with World War II edging ever closer, America was keen for new heavyweight king Joe Louis, only the second African American after Johnson to wear the crown, to this time beat the white man.

Two years before, Germany’s former world champ Max Schmeling had stunned Louis, who was deemed close to unbeatable at the time, when he stopped the “Brown Bomber” in a non-title fight in 12 rounds.

By June 1938, Louis versus Schmeling II was the biggest event in sport. Schmeling was the unwitting mascot of Adolf Hitler’s Germany with Louis, who had beaten Jimmy Braddock to win the title, the man to stop the richest prize in sport winding its way towards the Nazis.

Staged in Yankee Stadium, New York, in front of 72,000 fans, Louis opened as a 3/1 favourite despite the steady beatdown he’d endured in the first fight. Unlike Jeffries, however, Louis proved the bookmakers right with a showing that remains one of his most brilliant. And brutal.

Louis dropped Schmeling three times in the opening round, each time from sickening right hands, and that was all she wrote. Though Louis’ electric performance wowed those in attendance, a competitive contest it was not.

“As far as the length of the battle was concerned,” reported the New York Times, “the investment seats, which ran to $30 each, was a poor one.”

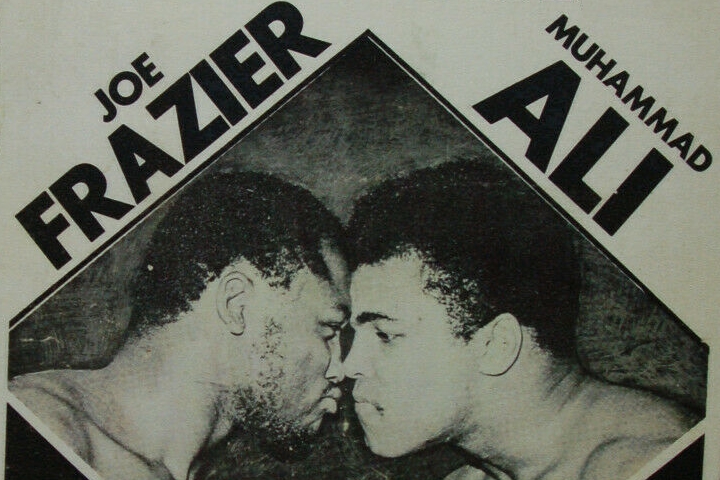

Though countless noteworthy heavyweight championship contests took place between 1938 and 1971 they were, as described previously, largely occurring automatically and therefore nothing like the world-stopping event that took place when Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali collided for the first time.

The reasons for the gargantuan appeal of Frazier-Ali don’t need retelling here. Though the subplots were plentiful – particularly given the fighters’ conflicting opinions on the Vietnam War – what the world wanted and expected was, very simply, a good fight.

Few sporting events, both before and since, have matched Frazier-Ali for worldwide interest. Fifty countries purchased broadcasting rights and commentary for the contest stretched to 12 different languages. It has been estimated that as many as 300 million people watched.

It’s doubtful that any of them could claim not to have been entertained and this remains the gold standard in heavyweight super fights because it is one of the few that truly delivered on the hype.

Ali bossed the opening rounds, Frazier came on strong in the fourth and it looked like anyone’s fight until the 11th, when “Smokin” Joe had his enemy in all sorts of trouble. There was still time for a fight back of sorts before the final round when Frazier uncorked that left hook and scored one of the most famous of all knockdowns.

In every imaginable way, it was the fight of the century.

Ali and Frazier had both long since retired by the time Mike Tyson came along in the next decade. And Tyson came with such astonishing force, nobody could stand in his way. By 1988, Tyson had cleaned up the mess created by the embracement of multiple sanctioning bodies and held the WBC, WBA and IBF titles. Only one viable challenger remained.

In 1985 Michael Spinks became the first reigning light-heavyweight champion to win a version of the heavyweight title when, in a huge upset, he took the IBF title from the great Larry Holmes on a close 15-round decision then repeated the feat, albeit contentiously, the following year.

Holmes was regarded as the man who beat the man and Spinks, therefore, became that man. A man that Tyson, despite holding all the belts, was yet to become. In 1987 Spinks relinquished the IBF strap to pursue a money-spinning bout with Gerry Cooney and the way he won that fight – Spinks drubbed Cooney in five – convinced doubters of his heavyweight capabilities.

The appetite for Tyson-Spinks was huge. Though not many were picking Spinks to win there was no doubt that he was regarded as the most formidable opponent of Tyson’s career. And at that stage of it, most fans were eager just to see “Iron” Mike in a competitive fight.

Billed ‘Once And For All’, Tyson-Spinks took place at Atlantic City’s Convention Hall on June 27, 1988. Each had a legitimate claim to the heavyweight throne and a sell-out crowd of 21,785 were there to witness with many more nearby to soak up the atmosphere. At the time, Atlantic City could boast $215 million in gambling revenue on a weekend yet, with Tyson and Spinks in town, that figure rose to $344 million.

Anyone who placed money on Spinks, however, would likely have regretted their decision as soon as they spotted him walk to the ring, crossing his chest and looking visibly uneasy. Tyson, who we now know was at his absolute peak, tore through his foe in 91 seconds. Spinks retired one month later and Tyson, soon to be consumed by the excesses of superstardom, never quite as good again.

The Nineties followed and though there were plenty of excellent matchups, the division lacked that defining fight. Evander Holyfield, Riddick Bowe, Michael Moorer and even a comebacking Tyson all flirted with the number one spot, but none of them managed to entertain the perennial number two, Lennox Lewis.

That changed in March 1999 when Holyfield and Lewis came together in Madison Square Garden. Well, you know the rest. A dull fight and a howling mad draw left the millions who paid good money to watch it feel decidedly short-changed.

We’ve had big fights in the division since then, of course. The biggest, perhaps, was when Wladimir Klitschko faced off with David Haye in 2011. With three belts on the line (WBO, IBF and WBA) it was the closest to ‘undisputed’ we’d had for many years but, yet again, the fight itself was forgettable as Klitschko used his superior size and strength to boss most of the 12 rounds.

Anthony Joshua’s thrilling win over Klitschko in 2017 bucked the trend but, with the Ukrainian inactive beforehand and Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury looming in the background, it didn’t feel like the all-conquering contest that Fury-Usyk is deemed to be.

The good news is that we’re at last going to see that all-conquering contest but the bad, if heavyweight history is anything to go by, the likelihood of it living up to the hype is slim.

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (17)