By Nick Skok

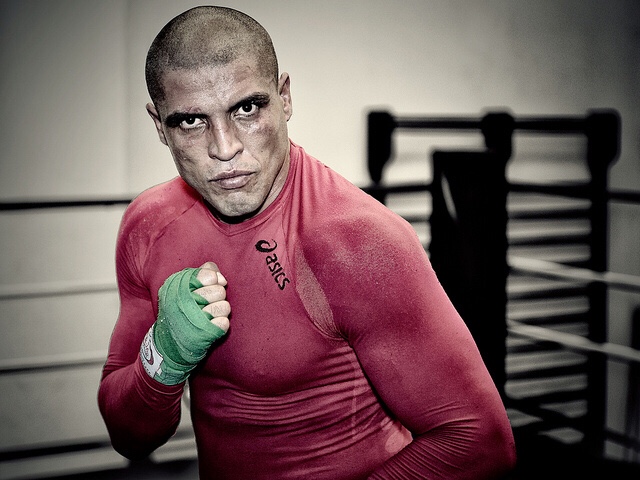

Domenico “Vulcano” Spada is an aged middleweight boxer from the Roman seaside region of Lazio. The former contender has stayed active enough though its mostly been a glorified hobby with professional fights coming against opponents not able to offer Spada a chance to rise or even be rated among any serious rankings within the sport should victory offer itself in any impressive manner or at all. That’s not to say the imposing figure never had a chance at all. Martin Murray and Marco Rubio were the crossroad opponents that Spada could’ve gained championship considerations with had he not lost in both opportunities.

Scrounging up a (43-7, 9 knockouts) record, his fiftieth fight would be his last in the ring, though not only because he lost in painful fashion to what one could only define as a stepping-stone match for a much younger opponent, but because Spada was swept up in an anti-mafia raid last month that was aimed at bringing down the powerful Casamonica clan around Rome. Spada had been engaging in a fight against what the Italian government and society says was for the soul of their culture and community. Now the government had connected with their most powerful blow yet, arresting Spada and thirty other mafiosos.

The mob and boxing has always had a fractious but intertwined relationship that can be traced back to storied figures like Frank “Blinky” Palermo and Frankie Carbo. The two were part of a group called “The Combination” that fixed boxing matches, with Carbo being referred to at the time as the unofficial commissioner of boxing. At the height of their reign, the underworld cohorts owned a majority interest in the contract of Sonny Liston; at their downfall they were sentenced to twenty-five years in prison with Robert Kennedy prosecuting them for conspiracy and extortion.

Movies too depict the historical context of the violent sport and the violent criminals that inhabit its shadows; some fictitious, some not so much. Rocky Balboa was muscle for the Philadelphia crime family, collecting debts for Tony Gazzo and trying to scrape out a living. Robert De Niro played an Oscar winning performance of hall of fame boxer Jake LaMotta who had famously ran with the Motown mob whenever he was in Detroit and notoriously threw a fight at Madison Square Garden against Billy Fox for the benefit of Blinky Palermo.

In a more recent real-life and less romanticized scenario, middleweight contender Avtandil Khurtsidze (33-2, 22 knockouts) was found guilty last month for violating the RICO Act (Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization) by acting as chief enforcer for a Georgian crime ring of savvy thugs that attempted to organize themselves into a durable wing for the Russian mob stationed out of Brighton Beach, Brooklyn.

Meanwhile in Rome, the Casamonica’s were controlling more than a ring; they had a $90 million dollar empire that was built on fear, murder, drugs, and kidnapping with Domenico and the rest of the Spada’s near the tip of their spear. Anti-mafia prosecutor Michele Prestipino said: “They didn’t need to use violence, the Casamonica name was enough” – though the Spada’s preferred the violence.

The Spada’s are a Romani people of Sinti origin, or colloquially referred to as gypsies. The Spada crime family gained international notoriety when Roberto Spada, brother of their leader Carmine, head-butt a reporter last winter while being videotaped, breaking the reporter’s nose. Roberto is now serving a six-year bid in a maximum security prison for that stunt.

His brother Carmine “Romoletto” Spada, was sentenced last October to ten years in prison for mafia related activity with one witness saying on a wiretap that Carmine had came to his restaurant with a flame-thrower and told him “this isn’t threatening you, it’s going to kill you.” Even with the brothers imprisoned, the crime family continued to function successfully under the guidance of the Casamonica’s.

At the Vulcano Gym, aptly named after Spada’s ring persona, the fighter trained in the sweet science but also attempted to corrupt government officials within its facilities. Located in Marino, about thirty minutes south of Rome, it was frequented by senators in Italy’s Five Star Movement “Movimento 5 Stelle” including Emmanuel Dessi. “I’m not a friend of Spada, I only went to his gym.” cried Dessi. The gym was seized as part of the bust and has been labeled “permanently closed” on internet searches.

Striking down Dessi’s claims and highlighting the influence Spada had, a video surfaced earlier this year purportedly showing Dessi dancing and partying with Spada in the coastal city of Ostia, fourteen miles outside of Rome and not far from Marino. The town has added significance as it was dubbed the “mafia capital” by police investigators two years ago and just before they disbanded their city council and placed it under direct Roman government control after it was discovered the officials there were under levels of mafia influence.

At this point Spada had already been banned from residing in the capital for being a known loan shark and was becoming more recognized for his role within the Spada crime family at their Ostia headquarters as opposed to his prize fighting that was now becoming a poster image for criminality and an insult to the government itself. After the now infamous encounter, the national news blitzed the senator, with government officials demanding he step aside from office, for fraternizing with the boxing hooligan.

Coincidently, it was the same time Ostia was being purged of corruption that the Casamonica’s came into public view in a manner even more grandiose than the headlines that gripped the national spotlight of the notorious town. Their leader Vittorio Casamonica had just passed and had what was both described as something similar to a state funeral and a movie scene, wrapped into one, with six black stallions pulling a carriage holding his glass incased coffin, while a low-flying helicopter dropped flowers on the crowd. Ceremoniously, an orchestra played the theme song from The Godfather along the funeral’s procession.

The next two years saw a crime wave in and around Rome that was directly the result of the Casamonica’s who had taken over the Rome cocaine distribution for the ‘NDrangheta’s – a mafia from Italy’s southern region of Calabria, that operate Europe’s largest drug trafficking organization. With their supplies and support, the Casamonica’s cast a wide umbrella that encompasses forty-three criminal families including the Spada’s.

During this campaign of crime, Spada fought five times, with three bouts taking place in Marino, including at least once at his own Vulcano Gym, winning on points all three times. Ironically, Spada complained about the fairness he was afforded in Mexico for his contest against Marco Rubio that in victory would’ve made him an interim champion.

Spada spoke to boxing journalist Ben Jacobs about possible scale manipulation during the lead up to that affair saying: “I mean, I work my ass off to make middleweight and then you rob me of two kilos on the scales? Two kilos is not a small thing, you know? I know that the scales were altered because just a few minutes before in the hotel I weighed 72.5 kilos (around 159.8lbs), then at the weigh-in I was 71kilos (around 156.5lbs).”

The narrative left some doubt as to whether or not Spada had been crying wolf and if it had played in any small part to his defeat. The Italian “Vulcano” was given one more shot against a name brand opponent but would succumb to a vicious cut and lose on points to Martin Murray. Spada didn’t take the loss well and disappeared from the professional scene for nearly two years before returning to fight in Marino.

Nearby in Ostia, the despair had begun to snowball with the Spada’s warring rival factions for control of the coastal city which they would eventually gain. Italian Interior Minister and deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini said the dangerousness and expansion of the Casamonica’s [and Spada’s among them] meant it could now be compared with notorious outfits including the Camorra in Naples and Cosa Nostra in Sicily.

The situation finally came to a head last month when the Pope himself visited Ostia to denounce the mafia. “Jesus wants the walls of indifference and ‘omerta’ to be breached, iron bars of oppression and arrogance torn asunder, and paths cleared for justice, civility and legality,” he said. Weeks later, the raid rounded up senior leaders with Domenico Spada among them.

Looking back on the Rubio fight, Spada was deducted points for using rough tactics that along with his subpar performance throughout the first half of the fight, put him in an early hole he couldn’t get out of on points alone; he’d need a quick and easy finish for any chance at victory. The parallels of using rough tactics in life outside the ring, for quick and easy money, all while lacking the same slickness he could’ve used against his tough Mexican opponent, Spada lands in the same place today as where Rubio left him in the tenth round of that night; at rock bottom and wondering what he could’ve done differently.

Contact the author via Twitter @NoSparring

ADD COMMENT VIEW COMMENTS (12)